Analyzing Legend of Zelda: Tears of the Kingdom’s game design

Freedom is meaningless without purpose

Recently, I came across this Kotaku article by John Walker, which explores the ongoing debate between open-world game design emphasizing “player agency” and more “curated, directed, deliberate narrative experiences.” The article highlights how the “freedom” of open-world games is often touted as inherently superior to the so-called “corridors” of linear design. However, Walker argues that both approaches have great value, and one shouldn’t be abandoned in favor of the other.

The piece was inspired by an interview with Ken Levine, the creative director of the Bioshock series. In the interview, Levine criticized the original Bioshock game, calling it “a very, very long corridor.” In contrast, his upcoming FPS, Judas, is designed to be “much more … reflective of players’ agency.” Now, while I have some thoughts about Levine himself, I’ll save those for another time. Here, I simply want to say that I wholeheartedly agree with the sentiment in Walker’s article. In fact, I’d even take it a step further: “freedom” in video games isn’t inherently a good thing, and “corridors” and “agency” are not mutually exclusive.

Reading the article brought to mind a particular game – a game I initially bounced off pretty hard after several hours but couldn’t get out of my head ever since. It’s part of a legendary series spanning decades, created by a beloved and talented developer. The game I’m referring to, of course, is The Legend of Zelda: Tears of the Kingdom. In this post, I want to explore why I believe its game design is fundamentally broken, and what “freedom” has to do with it.

The role of limitations in BOTW

I’m not the only one who has been disappointed by Tears of the Kingdom. This great video comprehensively critiques the game, covering nearly all of my gripes with it while also highlighting issues I hadn’t even considered. I highly recommend watching it. However, I don’t want to do a full review of TOTK here. Instead, I’d like to focus on the core aspects of its design philosophy that I believe undermine the game.

To understand the fundamental issues with TOTK, we must first examine Breath of the Wild and its core mechanics. BOTW’s defining strength – and its central, high-level mechanic – is exploration. The game is meticulously built around this principle: its gameplay flow, narrative design, and supporting mechanics all serve to enhance the experience of exploring a fantastical world.

Much has been said about BOTW’s famous “triangle rule,” a design philosophy where players are always drawn toward multiple points of interest, no matter where they’re in the game’s world. The triangle rule ensures players have a limited but meaningful number of objectives to engage with as they journey toward their main goal. These objectives – such as gathering resources, clearing enemy camps, discovering ruins, or finding shrines – are never overwhelming. Instead, they feed seamlessly into the game’s core loop, offering resources, combat encounters, lore, or simply satisfying player’s curiosity. This structure creates a sense of wonder and immersion.

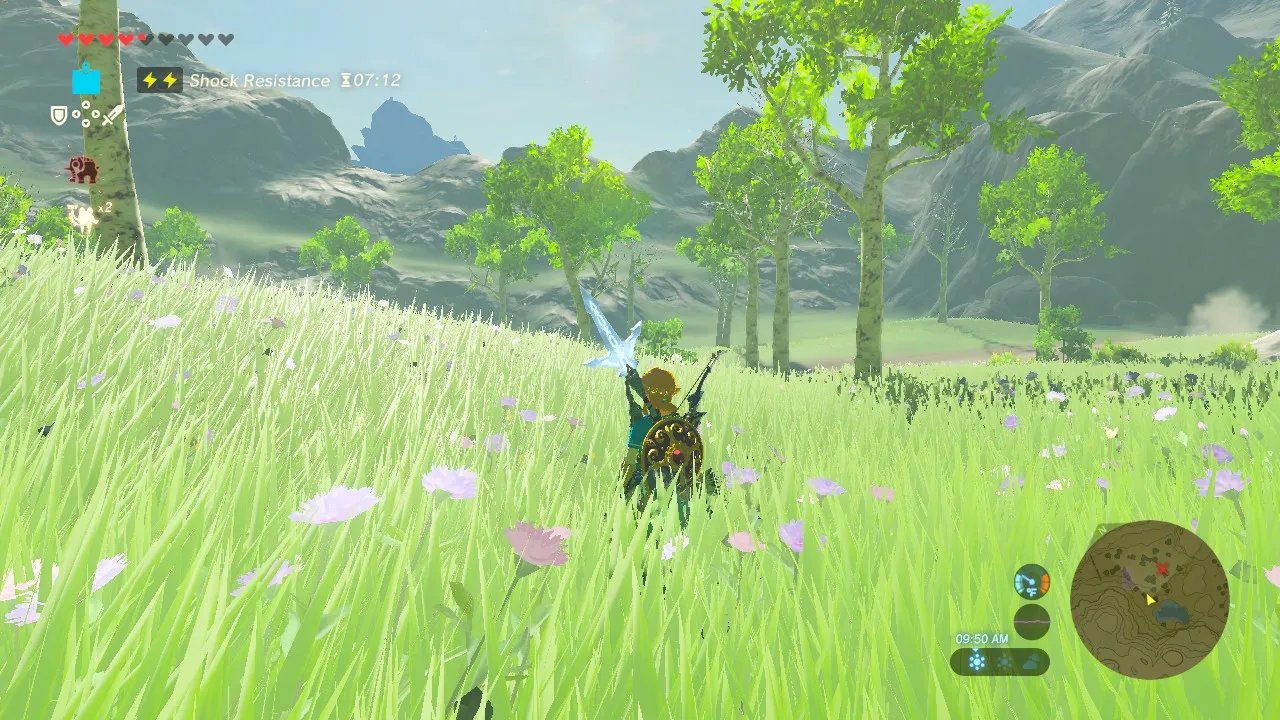

BOTW’s exploration thrives on its constraints, which force players to engage deeply with the game world. For instance, because movement options are so limited (relatively speaking, as compared to TOTK or a game like GTA), overcoming terrain obstacles such as mountains compel players to make meaningful choices. Do you scale the mountain and risk running out of stamina, or being caught by rain which makes climbing impossible? Do you take the longer route around and perhaps face enemies or other obstacles? Or do you gather resources and make fire to create an updraft and fly partway up – an option that might also be unavailable in the rain? These choices arise not just from the movement options available to players, but also from the limitations inherent to those options.

The game’s infamous weapon durability system is another example. While controversial, it serves the exploration-focused design – players have to be always searching the world for new weapons, because whatever they have in their inventory can be gone very quickly. Players must also carefully consider how to use their weapons, sometimes resorting to environmental tools or stealth to conserve resources. This system, while provides limitations, also tightly connects exploration with resource management.

Even the pacing of world traversal is deliberate. Early in the game, movement is slow, in a way forcing players to pay closer attention to their surroundings. BOTW has no heart items, so in order to be able to replenish their health players have to procure various resources via hunting, gathering, foraging, etc. This process feels natural and seamlessly integrates with the game’s exploration. For example, while exploring, a player could notice an apple tree along their path, stop by it for a few seconds, collect apples and maybe catch an unlucky lizard scurrying by. Those apples and lizards would help them to continue with the exploration. In order to collect resources players have to meaningfully engage with the world, at the same time, collecting resources feeds into other mechanics such as combat or crafting, creating a cohesive experience. As players progress and unlock faster travel options, like teleportation saddle and the Master Cycle Zero, they’ve most likely already explored the map thoroughly and have plenty of resources, so there’s really not much need for them to keep their noses too close to the ground. Basically, these faster travel options are limited to the late-game and because of this, the balance between freedom and meaningful engagement remains intact.

While moving through the world slowly players are becoming more grounded in it, listening to the sound of the wind, the rustle of the grass and buzzing of the flies, watching tree branches swaying and animals moving through the bushes. This “groundedness” makes it very easy to role-play as Link. Players truly feel like they’re exploring an unfamiliar world and surviving in the wilds. BOTW’s narrative design and lore presentation supports its exploration-focused gameplay. The world tells its story through its environment: the Akkala Citadel, the Forgotten Temple, 8 heroines of Gerudo, the outposts, and many other locations feel steeped in history. Of course, they don’t have that much going on for them aside from looking cool, but in a way this only adds to the mystery. The lore also feels cohesive and thought through. Zonai architecture and scattered memory cutscenes add layers of mystery and intrigue. This minimalistic approach to storytelling encourages players to seek out lore organically, enhancing the sense of discovery.

Some side quests in the game felt like the standard stuff you’d find in any open-world adventure. Others, however, stood out. I want to share an anecdote to show what I mean. While chatting with NPCs at the Dueling Peaks Stable, one thrown a casual remark about a bandit stash hidden in a nearby waterfall. It was an offhand comment, easy to overlook, but it piqued my curiosity. Intrigued, I’ve decided to explore the nearby area. Quickly enough I found a waterfall. Could this be the waterfall NPC mentioned? As I approached, my curiosity grew stronger despite the growing danger – I had to fight a few tough enemies on the way and even sneak past a Stalnox. Still, I pressed on. When I reached the waterfall, I noticed something unusual – an outline of what looked like a cave hidden behind the cascading water, a few meters above ground level. Climbing up to investigate, I found a small cave with a chest tucked inside. Inside the chest was a decently powerful sword, perfect for my in-game level at the time. When I returned to the stable, the NPC even acknowledged my discovery with a comment about the bandit’s treasure. This wasn’t a formal side quest—there was no quest name flashing on the screen, no quest-start jingle, no markers on the map, and no detailed objective in a menu. Instead, the game’s minimalist approach to quest design encouraged me to pay close attention to the world around me, interpret subtle clues, and explore on my own terms. This design choice transformed the experience. Rather than simply following a marker on the map, I had to engage directly with the game world in a meaningful way. The result? A far more memorable and rewarding journey.

BOTW’s success lies in its ability to balance freedom with constraints. At its best, the game feels like an authored, curated experience where players have meaningful choices. When the game works like a “corridor” (or I guess, a set of “corridors”) where you move from one objective to another, when you engage with the game in the exactly intended way, this is when the experience is at the highest point. Traversing a mountain, tackling an enemy camp, or deciding the next objective – all these moments balance agency with the designers’ intended flow. The limitations ground the experience, making the world feel immersive and the exploration rewarding.

However, this balance is very fragile, and can easily be shattered. For example, if you would introduce an ability for Link to somehow simply jump over mountains, it would invalidate the three choices (climbing a mountain, walking around it, flying using updraft + climbing the remaining distance) I’ve talked about above. It would disrupt the delicate interplay of mechanics. Such a change would invalidate key decisions, reduce engagement with other systems (like climbing), and undermine the grounded nature of exploration. In BOTW, limitations are not (just) obstacles; they are the foundation of its cohesive design.

In a way, BOTW’s main strength is also its main weakness. If you don’t care for exploration, the game probably won’t do much for you. This also essentially puts it into the “knowledge-based” game category, along with Outer Wilds and Return to the Obra Dinn (although, the “knowledge-based” aspect is much stronger in those games). This means that once you’ve explored everything there’s to explore the BOTW, the consecutive playthroughs feel significantly less fun. You can’t re-explore and re-discover the same thing twice. Well, unless you simply forget stuff. And, of course, this isn’t the only issue with the game. But while BOTW isn’t without its good share of flaws, it is undeniably a focused and coherent experience. Its design philosophy revolves around a clear vision, with (almost) every mechanic serving a deliberate purpose. By contrast, TOTK struggles to maintain this focus. Its expanded mechanics and systems often feel at odds with the core principles that made BOTW so compelling.

BOTW’s brilliance lies in its constraints – its ability to provide freedom within carefully crafted boundaries. TOTK, in attempting to expand on this formula, may have lost sight of what made its predecessor so special.

More is less

There’s a lot to be said about how limitations can fuel creativity. Here’s a good youtube video about how this principle applies to the arcade game design. In the case of TOTK, the game demonstrates how adding more “freedom” and choices doesn’t necessarily increase player agency, and in fact, can result in a worse experience compared to its predecessor.

I think that it’s fair to say that the majority of gamers and developers seem to believe that offering more options inherently improves a game. This mindset is in a way similar to survivorship bias: when people focus solely on the one side of the problem – the perceived benefits of freedom – while completely overlooking the importance of limitations. Recently, I had a conversation with someone on Bluesky, where they said: “give the players tools, let them have fun, bingo, good game design…” While this line of thinking isn’t illogical, I strongly disagree. Simply providing tools and making players find fun on their own without clear goals and constraints isn’t enough to create a compelling experience.

Here’s a thought experiment: imagine Mario 64, where Mario has all of his abilities and controls exactly the same, but instead of diverse, intricate levels, the game world is a single, vast, empty white room. Would this kind of game be fun? After all, there’re so many options! Mario can jump, triple jump, crawl, he can do all those cool acrobatic moves! So it might be fun at first, but after 5 or 15 minutes, the novelty would wear off. Without meaningful objectives or engaging challenges, the tools are rendered meaningless. I know this example is exaggerated, but it helps me make my point: player options alone do not make a game.

Let’s try another experiment. Take Gone Home, a tightly crafted narrative experience, and add 18 weapon types and a skill tree. Would this improve the game? Of course not. Those additions would feel out of place and detract from the immersive storytelling. Gone Home is successful because every element serves its purpose. So my point here, is that just adding more player options doesn’t necessarily improve a game. These options at least need to make sense within the game.

Next, let’s imagine a Metroid game that includes the Morph Ball ability but never requires it. Basically, what if a Metroid game could’ve been completed without ever using the Morph Ball. Would players ever use it, if it were optional? Would it have become one of series defining mechanics? Perhaps, someone would’ve played with it for a few minutes, maybe someone would’ve even done a Morph-Ball-only playthrough, but it would’ve been unimportant in the grand scheme of things. Just having a tool is not enough, its use needs to be meaningful. Metroid has limitations around how and where the Morph Ball mechanic can be used, the same is with double jump and each other game mechanic. It has very specific contexts for Morph Ball’s use, specific purpose and this is exactly why it’s such an important and versatile tool. You can’t jump through a tight hole, and you can’t use morph ball to get over wide gaps – these are inherent limitations of these mechanics which define the contexts of their use and make them meaningful. The game teaches players to use it and incorporates it into progression. Tools only gain meaning when their use is required and contextually relevant.

Now imagine Mario 64 again, but this time Mario can fly freely in any direction. Not just glide, as with the Wing Cap, but like properly fly. While it might seem exciting to give players more freedom, this addition would ruin the game’s core design. Mario games are built around overcoming obstacles and navigating levels. Unlimited flight would invalidate those challenges and dismantle the sense of accomplishment tied to traversal. Unrestricted freedom can easily undermine the structure and balance that make games enjoyable. Just adding more player options not only doesn’t always improve a game, it can ruin it.

I wasn’t entirely honest in my Gone Home example, because I think for that game, adding guns would have almost the same effect, as adding free flying to Mario – it would ruin the game. There’s no reason for Katie to have any weapons in Gone Home, and as story and immersion are very important parts of the experience, hurting them also significantly hurts the game as a whole.

Now, let’s get back to Tears of the Kingdom. TOTK embodies pretty much all of the “bad” examples above. For example, by introducing nearly unrestricted flying, via gliding platforms (Zonai Wing) or “hover bikes,” the game undermines the exploration and traversal that defined Breath of the Wild. Remember that example I gave in previous section, how introducing an ability for Link to easily get over mountains would destroy to the balance of mechanics? Well, that’s pretty much exactly what TOTK did! TOTK also specifically contradicts BOTW’s “triangle rule” in many ways. For example, the rule created curated experiences by limiting player’s view with landscape features, using them to guide players toward points of interest. However, this would only work if players stay on the ground. In TOTK, this rule is effectively abandoned, as players can easily ascend to heights unreachable in BOTW (for example, almost all towers in TOTK launch Link higher than the highest point in the entire of BOTW) and view every thing from above, significantly reducing the sense of discovery and reducing exploration to efficiency. The slow and grounded traversal is pretty much gone from the game (aside from the very early hours), and is replaced by flying fast through the sky directly to the points of interest.

Do the new mechanics add more options and freedom to the BOTW’s formula? Absolutely! But do they meaningfully improve the game as a whole? I don’t think so.

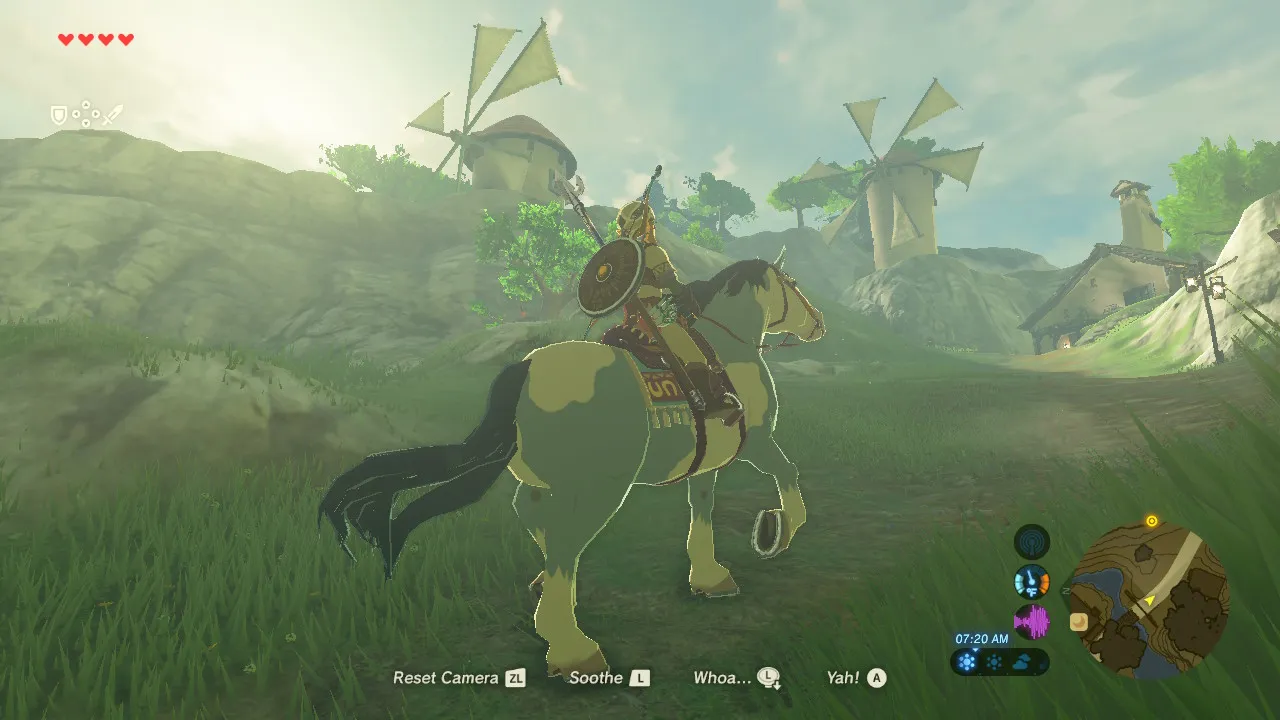

Many of the mechanics that TOTK has added are at odds with the old mechanics it had inherited from BOTW. For example, horses are now pretty much irrelevant compared to faster, easier flight options. To a certain extent, this also applies to climbing. Why bother climbing over an obstacle and worrying about the rain when you can just fly right over it? Weapon hunting and durability system have been mostly rendered irrelevant by fusion, as players can now create makeshift weapons out of abundant materials lying around, such as sticks and horns, which are good enough for most situations. Because of fusion players can almost always be certain they will have weapons powerful enough to get them through a fight, so the importance of looking for new weapons is diminished. Your sword is about to break mid-fight? Just fuse it with trash lying nearby and it’ll last longer! The weapon system in BOTW, even though it had a lot of problems, was also cohesive. Weapon fusion diminishes effect of durability, which had its own important role to play in the old balance of things. At the same time, it doesn’t solve the main gripes people had with the weapons in the first place, since they still do break, and there’re no unique and valuable weapons in the game at all, aside from Master Sword. It partially dismantled the old controversial but cohesive system, without solving any of its problems. At the same time it also introduced some issues of its own – such as poor aesthetics, needless complexity, menus constantly slowing down game’s pace, etc. TOTK’s new tools overshadow BOTW’s carefully balanced mechanics, making them feel obsolete.

TOTK also suffers from an absurd amount of bloat. You could cut the optional content in half, and most players wouldn’t even notice. While BOTW had its share of issues, such as a cooking system plagued by redundancy, TOTK has doubled down on this problem. For instance, combining a Cold Darner with a Monster Part and a Winterwing Butterfly with a Monster Part both produced the same heat-resistance elixir with nearly identical properties. Too many dishes offered the same effects, while others were so poorly balanced they were effectively pointless. Even with just 122 base recipes, BOTW’s cooking system felt like a bit too much. Now, TOTK inflates this number to a staggering 228 recipes – most of which are either redundant or useless, even in the early game. What is the point of this “choice” if it adds no value? And the same applies to everything else in the game. Take a look at combat: why does it matter if you’re fighting yet another horde of Bokoblins with a stick fused to a stone or a stone fused to a stick when the result is functionally identical? The same goes for arrow combinations. While the game boasts numerous combinations, in reality, there are only about maybe 14 distinct arrow types worth crafting – and even among those, several are barely useful. If there’s no meaningful difference between different options provided by the game, then the choices themself become meaningless. The illusion of variety without substance only serves to bloat the experience, undermining the very sense of discovery and creativity, once it inevitably wears off.

When it comes to puzzles, I have a hypothesis: having many ways to solve a puzzle inherently and unavoidably makes it easier. Let me explain. Imagine a game where you can take a limited number of actions, say 100. Now, picture a puzzle that can be solved by performing any one of those 100 actions. In other words, any action you take will solve the puzzle. Can this even be considered a puzzle? If no matter what you do, even if you pick actions at random, you can still solve it, then it lacks challenge by definition. Now imagine this: which puzzle is more difficult? One that can be solved by performing any one of 50 specific actions out of 100, or one that can only be solved by performing a single, specific action out of the 100? Even intuitively, you can tell that the puzzle with 50 ways to solve it is easier than the one with only a single. If you perform a random action out of the 100, your chance of success in the first case is 50%, but in the second, it’s only 1%. This logic, I believe, applies to puzzle design as a whole: the more restrictive a way to solve a puzzle is, the more difficult the puzzle becomes. Conversely, the more ways there are to solve a puzzle, the easier it is by its nature. I think, that when put this way, my hypothesis sounds obvious, doesn’t it? If we take a look at something like Rubik’s cube, for example, then we’ll see that there’s only one way to solve it – by rotating its sides. Of course, you can try disassembling it with a screwdriver and then putting it back together, or maybe try warping it through a fourth dimension or something, but that’d be considered cheating. And yet, despite its very restrictive design, it’s such a great puzzle that gives a lot of freedom for how it can be approached. Despite only having one way to solve it, Rubik’s cube is timeless, and provides with nearly endless entertainment. On the other hand, I think that at a certain threshold, once you introduce too many possible ways to solve a puzzle, it becomes almost impossible to make it genuinely challenging. Of course, while designing a good puzzle with only one way to solve it is hard, designing a good puzzle with multiple ways to solve it is exponentially more difficult. Now, to return to the subject matter of this post, the puzzles in TOTK are relatively weak on their own. Nintendo aimed for a level of freedom and player choice that allowed for countless solutions, but this very openness undermined the potential for truly challenging puzzles. Even if Nintendo had tried to make these puzzles more intricate, retaining the same degree of freedom and options would have made this nearly impossible. On the other hand, some of the best, most rewarding, and intellectually challenging puzzle games, such as Return of the Obra Dinn, typically offer a very limited number of solutions to their problems. Their strength lies in how restrictive they are, demanding specific and well-thought-out answers from players. This restrictiveness is what makes them great. By contrast, TOTK’s open-ended design sacrifices the depth and difficulty of its puzzles, resulting in a less satisfying experience, especially for those seeking a proper intellectual challenge.

Taking all this into consideration, I think it’s fair to say that TOTK doesn’t build on BOTW, instead it dismantles its predecessor’s strengths and replaces them with an incoherent mishmash of superficial additions that often clash with the game’s tone and mechanics. While players can choose to avoid these new features, their prominence makes them impossible to ignore. This isn’t just a “you control the buttons you press” type of situation. Those new mechanics are at the forefront of the intended TOTK experience. Evaluating a game requires a holistic approach, much like judging a song. Imagine you listen to a song which is very good, the only problem is that it has disgusting fart noises every 30 seconds. There’s no way around this, it would’ve been a huge issue, even if the rest of the song is good. Similarly, bad mechanics drag down the entire game, no matter how optional they may seem.

Many of the new mechanics also feel out of place. Just like Gone Home isn’t a game about shooting guns, Legend of Zelda never has been about building cars, mechs and Korok death machines, but here we are.

Lastly, TOTK has many other issues going on for it, in addition to the “bad freedom” mechanics. It recycles BOTW’s map, which diminishes the joy of exploration. Familiar locations lose their mystery, and the lore no longer matters. The story is weak, and its delivery undermines immersion. Flying around on absurd contraptions, wielding comically fused weapons, breaks the immersion and roleplaying elements that grounded BOTW.

In the end, Tears of the Kingdom highlights the importance of thoughtful design. Simply offering more freedom or tools doesn’t guarantee a better game. Without meaningful limitations and purposeful design, “more” often ends up being less.

There’re different kinds of creativity

If you study TOTK’s promo materials, reviews, and gameplay, you’ll likely conclude that the game is built around core idea of emphasizing creativity, player expression, and experimentation. In fact, its defenders often argue that disliking TOTK’s core mechanics indicates a lack of creativity. Some people even convince themselves that they only dislike the game because they’re uncreative. Here’s a Reddit post demonstrating this kind of thinking. Despite title saying “unpopular opinion”, I think this kind of thinking is pretty widespread, actually. I also want to quickly note, that the rhetoric in the post is deeply flawed. Creativity and rationality are not opposites, they complement each other. But I digress…

Creativity is a broad and tricky concept. At its core, it’s about creating something new. I’m not endorsing Rick Rubin here, however his definition resonates with me: to him creativity is “an integral part of everything one does.” Whenever you do something subjectively new – something you haven’t done or known before – you’re being creative. For example, taking a new route home can be a creative act. By this definition, everyone is creative to some extent. However, not all creativity is equally meaningful.

Imagine painting Swiss Alps on your face with ketchup. Technically creative? Sure! But meaningful? Probably not. What about playing with building blocks? Studies show it fosters creativity in children, but would you enjoy doing it alone as an adult? What if you strapped a Barbie or Spider-Man toy to a firework just to see how far it flies before exploding? Creative? Yes. Fulfilling? Likely not.

This illustrates the distinction between different kinds of creativity. Some acts of creativity feel purposeless and uninspiring, especially for adults. This is the kind of creativity TOTK leans into most often. Take its propping-up-sign side quests. The task is insultingly easy, it requires no meaningful engagement from player, making accomplishing it feel unfulfilling. The resources are even almost always conveniently placed nearby by game designers, and if you have a levitating platform, it becomes even more trivial. Worse, this quest repeats 81 times. As Feeble King pointed out, a puzzle ceases to be a puzzle when its solution is provided or when it’s repeated several times. It becomes routine, a time-waster. Can it be creative? Technically, yes. Is it meaningful or rewarding? Not really.

TOTK’s vehicle-building system exemplifies this shallow creativity. When it comes to the build mechanic, the game rewards speed and efficiency. This is reinforced by the fact that player’s constructs are meant to be disposable, disappearing when you reload a save or enter a shrine, and even more prominently emphasized by the Autobuild. Why spend 15 minutes building a complex contraption when a hover bike does the job better and faster? The game offers freedom, but there’s little incentive to explore it meaningfully. You can fight enemies with a poop on a stick or a two-hour-built Gundam – either way, the outcome is the same. This lack of extrinsic reward makes the creativity feel hollow.

Once again, I can’t help but think how limitations (in addition to the ones that are already in the game, such as energy limits, and limited resources) would’ve made for a better feeling mechanic that would’ve truly fostered the feeling of creativity. None of the game’s situations require players to assemble anything particularly complex or push their imagination to their limits. The game itself never sets goals for the players requiring them be really creative. Let’s take traversal, for example. Even if the hover bike wasn’t available as an option, building cars is still undermined by flying via towers and gliding platforms. Not to say that Link himself has plethora of movement abilities, such as gliding and climbing. And, of course, players can always fall back onto using horses, which is often faster and more fun than building a silly looking self-propelling carriage. However, what if we introduce limitations to this system? If we remove Link’s abilities to glide and climb any surface, and also make it so that towers don’t launch him high into the air, this would immediately make the building mechanic more valuable. Now, players would’ve had to carefully manage their available building components and rely on building machines to navigate the world and scale the mountains. If we remove horses, then silly cars would remain as the only way to get around the world on land, and this would’ve made building them more fulfilling. The same applies to building components. For example, what if we introduce limitations to the fan building component available to players since the very beginning of the game? What if we split it into 2 kinds of fan, a weak fan that’s exactly like the fan that’s already in the game, except it can’t be used to build flying vehicles, and another type of fan which becomes available in the very late game, that would allow building hover bikes and other flying vehicles? This constraint, in addition to already existing ones such as limited Zonai Charges in the beginning of the game, not only would’ve created a better sense of progression, it would’ve forced players to think more about how to traverse the game and use their imagination. Players would’ve had to build different vehicles for driving around the world, for climbing, for swimming, for flying. Now, whether this would’ve made for a better game is another question, but it’s indisputable that adding limitations would’ve made the building mechanic feel more meaningful.

Perhaps there’s some intrinsic motivation to be found in TOTK’s building mechanic. However, the process itself feels clunky, slow, and not inherently enjoyable. Worse still, as I’ve said before, it exemplifies the kind of meaningless creativity I’ve mentioned earlier. You’re not crafting a masterpiece or contributing to anything of lasting value, you’re neither improving your life nor the lives of others. In truth, it often feels like a waste of time. The mechanic isn’t intellectually challenging or particularly fulfilling. Sure, it might be amusing for 20 minutes to build something silly, like a d*ck spinning robot (which, let’s be honest, breaks the game’s immersion). You might post your creation on social media for a quick laugh, but chances are you won’t invest time in building anything as complex again. In fact, I think that the building mechanic is mostly enjoyable when you’re doing it for an audience, whether that’s posting on social media or streaming. Take this Dunkey’s video, for example. There’s a a very small chance anyone would spend hours goofing around and constructing these ridiculous machines, most of which don’t even work as intended, unless it was for the sake of sharing this experience with others. While this kind of dynamic is great for the game’s marketing, it’s not necessarily good for the game itself. If there were no audience and no way to share clips, would you genuinely find joy in building a Korok “death machine”? Or would you play with it for 5 minutes and then move on?

Well, to be completely fair, some players do genuinely enjoy pushing the limits of the system to construct ridiculous and elaborate machines. By all means, hats off to them for their creativity and dedication. However, these players are a very small minority. So unless you don’t find this playing-with-building-blocks-type of creativity intrinsically rewarding (if you do, that’s absolutely fine!), then the mechanic has very little to offer for you. And, as I already mentioned, the game itself offers no real acknowledgment or reward for those efforts. Whether you craft a functioning mech or a simple hover bike, the game treats both equally. This lack of meaningful recognition makes the building mechanic feel ultimately hollow and inconsequential, for those who don’t simply enjoy the clunky process.

The experimentation aspect suffers similarly. In BOTW, physics felt intuitive – objects behaved almost exactly as they do in real life, making things very predictable. TOTK complicates this with arbitrary mechanics. For example, combining an arrow with an eyeball makes it home in on targets. But how would you predict this? After all, in real life, eyeballs don’t enhance arrows, at least as far as I know. This forces you to experiment aimlessly until you understand the system. This trial-and-error process isn’t engaging, it’s tedious. Most combinations yield unremarkable results, and the system obfuscates its few genuinely useful options. Building follows the similar pattern. Creations often fail to work as expected, requiring you to learn how the system works exactly, instead of relying on your intuition, which is required to make experimentation meaningful. Instead of fostering discovery, this feels frustrating and inefficient.

Many people respond to criticisms of TOTK by simply claiming that players are “engaging with the game wrong.” Essentially, they argue that if you’re not having fun, it’s your fault. While this argument can hold water in some cases, it only goes so far. Certain games – like shmups or fighting games, for example – aren’t immediately approachable and require effort to learn and master. However, these games reward that effort with immense satisfaction and enjoyment. TOTK, by contrast, often feels like it rewards you with boredom, which might even be intentional – but I’ll return to that idea later. A variation of this defense is the claim that players “optimize the fun out of the game” by relying on efficient solutions, such as building hover bikes instead of riding horses. This argument doesn’t hold up either. First, as I’ve already discussed, the process of creating elaborate vehicles in TOTK often feels unfulfilling and is discouraged by the game itself, which prioritizes efficiency with mechanics like Autobuild. Second, if we try to play the game pretending like some mechanics aren’t there, well this just brings me to my argument that the game’s core mechanics are too central to ignore. A game should be judged holistically, and the experience it offers should stand on its own merits. For example, if the only way to enjoy TOTK is to treat it as though it’s Breath of the Wild – essentially playing it like its predecessor – then what’s the point? Doesn’t that make TOTK redundant? Personally, I’d rather replay BOTW than approach TOTK in that way.

Given the chance, I want to mention something. There’s a phrase that often gets thrown around: “Given the opportunity, players will optimize the fun out of a game.” This phrase originally belongs to Civilization IV designer Soren Johnson. I find this notion somewhat flawed. I think, that a truly great game design ensures that optimization itself is fun. Take the chaining mechanics in DoDonPachi, for instance, where players actually have to meticulously study every pixel of the game to maximize their performance and achieve the highest scores. This transforms optimization into an engaging, rewarding process. And this principle isn’t exclusive to arcade games. Consider the optional Weapon bosses in Final Fantasy VII. These encounters demand that players min-max their resources and push the game’s mechanics to their limits. The result? A deeply satisfying and rewarding experience. Bringing this back to TOTK – in contrast, it struggles to make optimization enjoyable. Its systems often feel shallow, offering efficiency at the cost of engagement. A great game invites players to experiment and optimize without sacrificing the core sense of fun, and that’s where TOTK misses the mark.

In summary, TOTK’s approach to creativity often feels shallow. The freedom it offers lacks meaningful rewards or intrinsic satisfaction, making its core mechanics unfulfilling for most players. Creativity can be fun, but only when paired with purpose – and that’s where TOTK falls short.

So what is at the core of TOTK’s experience?

TOTK offers players a wide array of options, but most are either meaningless within the context of the game or actively undermine each other. The creativity and experimentation it promotes feel shallow and unfulfilling. The plot is weak and inconsequential, the characters – particularly NPCs – are grating and irrelevant, and the lore is thin and contrived, rendering it equally unimportant. Even exploration, one of BOTW’s standout features, feels devalued in TOTK, along with many mechanics tied to it. Creativity itself is often pointless, as the most straightforward solutions tend to be the most effective.

So, what is at the core of TOTK? Instead of structured “corridors” or interconnected “lines” and “triangles,” the game is built like a cloud of disconnected dots – bite-sized chunks of content such as caves, sign-propping quests, Korok delivery challenges, shrine puzzles, and so on. It’s a game centered around mindless, repetitive activities. It lacks significant challenge, and its much-touted creativity mechanics are as engaging and meaningful as doodling in the margins of a notebook.

Taking all this into account, I come to the conclusion that TOTK is really a game equivalent of watching TikTok content sludge, or watching NPC livestreams. It fits into what I call the “boredom slop” category. Despite sounding kinda bad, “boredom slop” games aren’t necessarily bad at all! These are simply low-engagement games built around addicting routine mechanics. They don’t require players to connect deeply with the story or characters – some of these games don’t even have a plot at all. They don’t demand strong engagement with their mechanics, and digging too deeply often exposes their fragility and shallowness. Nor do they require physical engagement, such as sharp reflexes or precise motor skills, or intellectual engagement, like advanced problem-solving or deep strategic thinking. Instead, these games revolve around repetitive, dull activities that, while requiring minimal effort, are designed to be addicting.

This category is broad, and many games from various genres fall into it. Some games in this category are genuinely good, such as Minecraft or Animal Crossing, which have more coherent, well-integrated mechanics that complement one another compared to TOTK, btw. A lot of MMORPGs and “cozy games” also fit this mold.

In itself, being a “boredom slop” game isn’t inherently bad, as I’ve already mentioned. What makes it all suck in case of TOTK, however, is that it’s not just any game, it’s the Legend of Zelda. The series carries a legacy of innovation, depth, and meaningful player engagement. And while I’m always in favor of change, I don’t think this is a fitting direction for the series.

The conclusion

The Legend of Zelda: Tears of the Kingdom is a truly fascinating case study in game design. While it introduces new mechanics and aims to expand player creativity, it sacrifices the carefully curated balance and coherence that made Breath of the Wild so impactful. Freedom, as Tears of the Kingdom demonstrates, is not inherently valuable without purpose and meaningful limitations. By prioritizing open-ended experimentation over the immersive, focused exploration that defined its predecessor, the game ultimately feels directionless and less satisfying.

This isn’t to say that player agency or creativity are unworthy goals in game design – far from it. But they must serve a greater purpose within the game’s structure. Breath of the Wild succeeded because it married freedom with intentionality, inviting players to discover and engage with a world that felt alive, mysterious, and at least somewhat rewarding. Tears of the Kingdom, while ambitious, struggles to replicate that magic.

In the end, perhaps the most important lesson from Tears of the Kingdom is that good game design thrives on balance. Freedom needs purpose, creativity needs meaningful constraints, and every mechanic should contribute to the core experience. Without these elements, even a game with the most extensive list of options can feel empty and aimless. If BOTW was supposed to be our glimpse into a bold new direction for the series, TOTK has effectively demonstrated that that direction leads to a dead end.

2025-01-11